Rural health care in developing countries: AUNP Family Medicine Training Curriculum Development Project

Nitaya Wongsangiem Tanuwong,1. Sawanee Tengrungsun,1,Sing Menorath,2 Alongkone Phengsavanh,2,Garth Manning,3 Han Aarts4

1Office of Community and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand; 2Postgraduate Study and Research Office, Faculty of Medical Sciences, National University of Laos, Vientiane, Lao PDR; 3International Development Programmes Office, Royal College of General Practitioners, London, United Kingdom; 4Maastricht University Center for International Cooperation in Academic Development (MUNDO) Office, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Key words: curriculum development, developing country, family medicine training, rural health care, South-east Asia

Introduction

Lao People Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) and Thailand are two neighboring countries in South-east Asia with bonds and relationships that have developed for over 200 years. Both are now active members of ASEAN.

In January 2000, the European Union and the ASEAN University Network launched a 6-year joint initiative ASEAN-EU University Network Program (AUNP).1 The program’s aim was to improve co-operation between higher education institutions in European Union Member States and ASEAN member countries, and to promote regional integration within ASEAN countries. In 2003, the AUNP granted cofinancial support for a project titled ‘Higher and continuing family medicine curriculum development for rural physicians in developing countries’, which was submitted by Family Medicine Division, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand.2 In collaboration with Faculty of Medical Sciences, National University of Laos; Maastricht University, the Netherlands; and the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), United Kingdom, the project aims to develop an innovative curriculum for postgraduate training in family medicine, which will incorporate a distance learning module. This method of teaching and learning is new to medical education in the region. The project target groups, in Lao PDR and Thailand, are regional and provincial hospital doctors who will act as local facilitators, and practicing rural doctors who are to be trainees of the curriculum. The ultimate aim is to improve both health care quality and the standard of the current rural health service through better trained doctors.

This review aims to examine the health profiles of Lao PDR and Thailand and their respective health systems. It also gives an overview of current family medicine education within each country and summarizes the AUNP-funded project.

Health Profiles and workforce numbers

Figure 1 shows maps of the two countries. Seventy percent of Lao PDR terrain is mountainous with approximately two million people (30% of the population) living in rural areas and in poverty.3 Access to, and provision of, medical care is limited by poor or no infrastructure support and a diversity of cultures, languages and beliefs of the approximately 47 different ethnic groups. Essential primary health care in rural areas is provided by health personnel working in 654 health dispensaries. These health staff are limited in number, have received no proper training and work with limited resources. A similar situation exists in remote areas of Thailand, with the population having to travel for hours to access a medical doctor. Health centers numbering 9738, operating at the grassroots level, suffer shortage of resources but are capable of providing essential public health services to the community due to good infrastructure support systems and a good centrally planned scheme.

Table 1 summarizes the health profiles of the two countries.4–6 A major difference between the two countries is that Thailand is moving towards a non-communicable disease predominance. Infectious and communicable diseases, such as diphtheria and tetanus neonatorum, have largely been eradicated in Thailand but are still prevalent in Lao PDR.

Medical services

Lao PDR

In Lao PDR, over half the district hospital doctors are medical assistants. There is only one medical school and the medical degree program started in 1966. It produces approximately 100 medical graduates each year. All Lao medical doctors, working in 131 district hospitals, begin practice positions immediately after graduation, and 90% of these receive no further training. In addition approximately 60% of doctors working in the 18 regional and provincial hospitals have no postgraduate training.

There are now six residency training programs currently running, with 46 available posts, all of which receive foreign aid. They also receive limited funding from the Ministries of Health and Education (MOH, MOE). The first program, pediatric residency, started in 1997. The two most recent, obstetrics-gynecology and ophthalmology, started in 2003. Family medicine has just been introduced into the medical education system by a 2-year internship program which started in January 2005.7 This is supported educationally by Calgary University in Canada. After training, all specialists will be assigned positions in the teaching, regional and provincial hospitals. Table 2 summarizes the current health service system in the two countries.

Thailand

Thailand graduates around 1300 medical doctors annually from 13 public and one private medical school. This includes 300 doctors from a special program – The Collaborative Project to Increase Production of Rural Doctors (CPIRD) – of the Ministries of Public Health and Education. This project is due to run between 1995 and 2006 and aims to produce 3000 rural doctors. It is based on three strategies of rural recruitment, community training and hometown placement. All new medical graduates have a compulsory 1-year internship and 2 years service in community hospitals. After completion, there are 1114 residency postgraduate training posts available, offered by 33 training programs in 41 specialties and subspecialties. At least 1–3 doctors in most district hospitals have postgraduate specialty training or education in epidemiology or public health.

Dilemmas facing primary care

In spite of the progress detailed above, the primary medical care system of the two countries has specific problems.

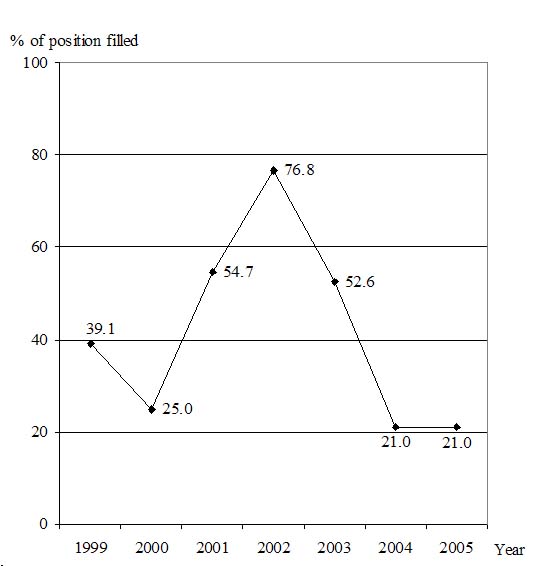

In Lao PDR, there is a limited budget for new doctor positions.The family medicine residency training program, which replaced the general practice program in 1998,8 is not preferred by young doctors, who seem to be gravitating toward specialist training (Fig. 3).

In Thailand, there is an increasing number of doctors resigning from the government service each year, especially among the new graduates who have finished their compulsory training, and who either leave to undertake residency training, or to work for private hospitals.

Hence, there is an urgent need to upgrade knowledge and skills of district hospital doctors in Lao PDR; and to motivate young doctors in Thailand, who are already serving in community hospitals and have already established doctor–patient–family–community relationships, to continue working in this area. A postgraduate training scheme, which can be delivered to their workplace, causes minimal disruption to their community contact and work-life, and which is relevant to their practice, would hopefully address some of these problems and keep doctors in the community, working with pleasure and pride.,9

AUNP project: cooperating to produce a challenging and innovative family medicine training curriculum

The 2-year project started in January 2004 with the aims of developing and implementing a region-specific curriculum to train local facilitators and create a trainee curriculum for practicing rural doctors. The outcome of the project would be a training curriculum acceptable to each ASEAN partner.

The first phase comprised three 4–7 day medical education and curriculum development workshops, run over 1 year. The workshop tutors were educational experts from both local and European country partners. The objective of the workshops was to train 30 doctors, who were currently working in regional/provincial hospitals in all regions of Lao PDR and Thailand, as local facilitators. The international ‘train of the trainer’ (TOT) course has been developed by RCGP, UK and used in several Asian, Middle-East and African countries. Doctors were invited to apply to participate in the workshops, provided they fulfilled participant criteria: age less than 45 years, postgraduate training in any specialty or family medicine; and English proficiency. Equal numbers of both genders was also sought. The workshop topics included: principles of adult learning, learning styles and teaching methods; how to plan, prepare and deliver lessons; giving feedback; assessment and evaluation; practicing skills such as teaching and communication; learning needs assessment; and curriculum development process.

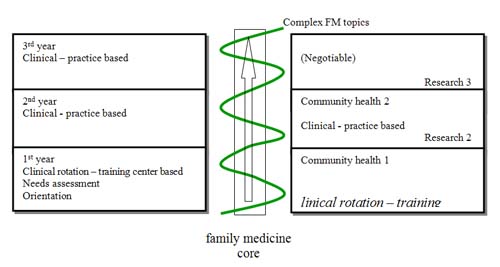

With tutors’ guidance, these 30 doctors then developed an in-service family medicine training curriculum. They brainstormed in small groups which consisted of various combinations of numbers of: GPs/FPs to specialists; teachers and practitioners; Laos and Thais. The agreed outcome was a five-star doctor capable as a care provider, a decision-maker, a communicator, a community leader and a manager,10 plus research abilities.

The participants shared ideas and identified the type of curriculum and the contents, according to each country’s needs and methods to deliver them, and the communication and assessment/evaluation methods. While the curriculum must be suitable for rural doctors in their respective countries, many of the learning contents shared the same core. A survey of the training interests and learning needs of doctors working in community/district hospitals in their provinces within both countries, was planned, the results of which will be incorporated into the curriculum.

These workshop participants then organized shared responsibilities to create learning materials, which will be tested later in the second year of the project. The learning material formats, complete with facilitator guides, trainee worksheets and evaluation forms, were designed to be delivered by post or, where possible, by the Internet. Timing and frequency of facilitator–trainee contact and skills/procedural training were also scheduled. A committee from each institute will comonitor and coevaluate the curriculum annually. The curriculum draft is shown in Fig. 2.

Conclusion

An AUNP-funded project to develop an in-service family medicine training curriculum is ongoing in Lao PDR and Thailand. It used a cascade design by creating local facilitators from practicing doctors in regional/provincial hospitals. These doctors, by participating in the curriculum development process possess a sense of ownership. After approval and implementation, they can cooperate in curriculum management with full commitment and as knowledgeable local facilitators for rural trainee doctors, with the desired outcome of improving health care provision to the rural population of Lao PDR and Thailand.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the AUNP for the grant support of this project. Our gratitude to the deans of both faculties in Lao PDR and Thailand who gave full support to all our activities. Our thanks extend to the representatives of the Ministries of Health of the two countries who also gave valuable advice for the sustainability of the curriculum. Most appreciated are the 30 trainers from Laos and Thailand who worked energetically and enthusiastically to support the project. Their views and contributions from their experiences in rural areas were invaluable to us. A part of this paper was presented at the World Wonca Conference in Orlando, Florida, USA, October 2004.

References

1 http://www.europa.eu.int/comm/europeaid/projects/aunp_en.htm

2 ASEAN-EU University Network Program. Grant contract. Contract Number: ASIA AUNP – ASE/B7–3010/1997/, 2003; 0178–12.

3 http://www.aseansec.org/membercountries

4 World Health Organization. The World Health Report, 2003. Shaping the Future. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003.

5 World Health Organization. The World Health Report, 2004. Changing History. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004.

6 Ministry of Public Health. Thailand Health Profile, 1999–2000. Bangkok: Bureau of Policy and Strategy, Ministry of Public Health, December 2002.

7 Faculty of Medical Sciences. Document: Intern Program, August: 2003 Vientiane, Lao PDR: Faculty of Medical Sciences, 2003.

8 Thai Medical Council. Document: Family Medicine Residency Training Curriculum, June 1998. Bangkok: Thai Medical Council, 1998.

9 Boelen C, Haq C, Hunt V, Rivo M, Shahady E. Improving Health Systems: The contribution of Family Medicine. A Guidebook. A Collaborative Project of the World Organization of Family Doctors (Wonca) and The World Health Organization (WHO). WONCA 2002.

10 Boelen C. Towards unity for health: challenges and opportunities for partnership in health development. A working paper. Geneva: World Health Organization. (unpublished document. WHO, 2000a/EIP/OSD/2000.9).

11 Records from College of Family Physicians of Thailand, 2005.

Table 1 Details and health profiles of Lao PDR and Thailand4–6

Country profile |

Lao PDR |

Thailand |

Table 2 Health service system in Lao PDR and Thailand6

Level of care |

Lao PDR |

Thailand |

Primary health care 1. Self care

2. Village level

3. Sub-district level

Secondary care

Tertiary care

|

Folk medicines, drugs from grocery stores

|

Drugstores, folk medicines

Community PHC centers, village health volunteers

75 provinces: 25 regional and 72 provincial hospitals, private hospitals |

Fig. 1 Maps of Lao PDR and Thailand

Fig. 2 Curriculum draft. Eight content areas: Family medicine core curriculum; Basic and advanced; Advanced primary care including medical laws and ethics; Management of common health problems in primary care; Community and population health issues; Case-based and evidence-based medicine; Health and clinical economics; Organization and management; Research methodology and research ethics. Trainee-Trainer contact every 4–6 weeks.

Fig. 3 Percentage of family medicine offered positions filled.11 Four training programs in 1999, 25 programs in 2001. Ministry of Public Health support for health care reform policy launched in 2001 for 2 years

^top